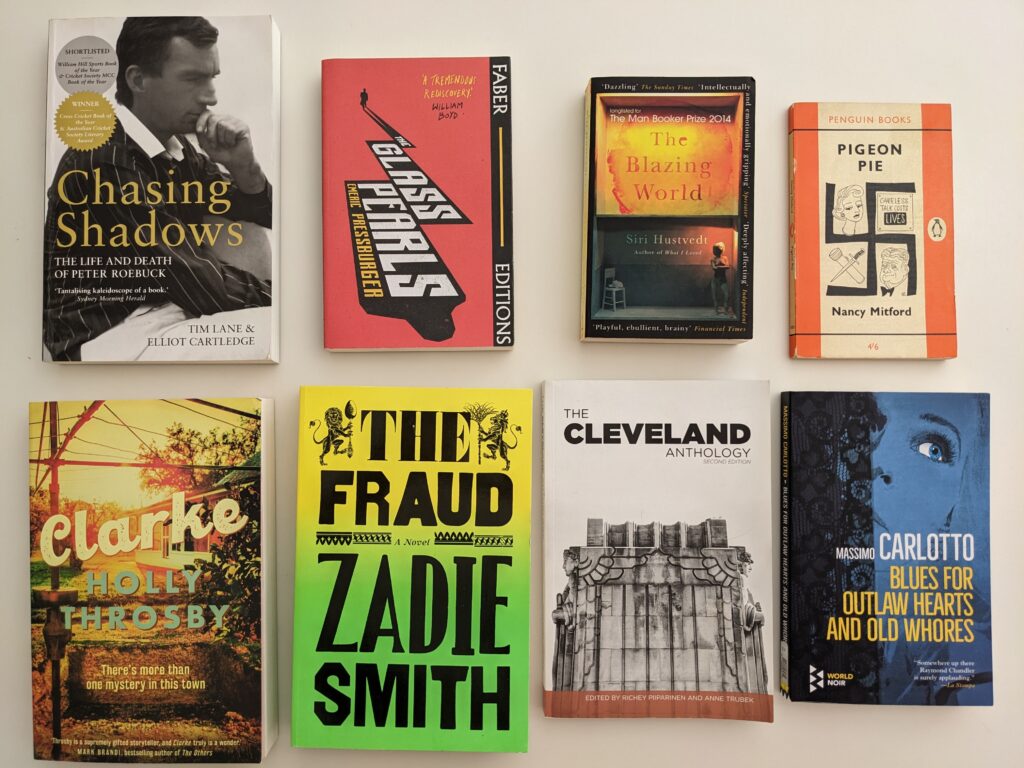

Fancy me reading a cricket book! I’ve struggled to be interested in the sport ever since the rotten, mean-spirited Glenn McGrath days really, but this Peter Roebuck biography Chasing Shadows had enough intrigue, and the legitimacy of Tim Lane helped. I’m glad I read it, though there are plenty of discomforting moments where I was conflicted between the various trains of thought (people took advantage of his generosity and blackmailed him vs. he had made too many enemies and was killed vs. he knew he’d be crucified for his sexual indiscretions). A brilliant, driven and compartmentalised man, whose battlescars eventually got the better of him. Wonderfully done – 4.5 stars.

The Glass Pearls (1966) by Emeric Pressburger was a delight – the German “Karl Braun”, living an anonymous life in post-war London becomes increasingly paranoid about pursuing Nazi-hunting agents. I loved the insights into his co-workers and odd, miserly housemates – especially the business-minded, deal-making Strohmayer. Compelling and enthralling till the end. 5 stars.

The Blazing World (2014) by Siri Hustvedt is a book I would have finished in my 30s when I was more patient (and forgiving), but boy, did those 186 pages before I stopped test me. Reading the Goodreads reviews afterwards, I was very happy I gave in at the half way point. Based on a wonderfully cynical premise about the nature of the art-collecting world, a female artist passes off her maniacal and obsessive art installations as the work of various other suitable male counterparts to prove industry biases. It was dense, cerebral and overly serious, which started to become repetitive and harping at a certain point. Well written, but 3 stars.

It took me a while to warm to the short, farcical, spy thriller Pigeon Pie (1940) by Nancy Mitford, but I eventually got there. A shallow societal madam in London realises almost too late that her husbands’ friends are Nazis and are planning evil deeds. A satire on between-the-wars society with a quirky premise that only just works. Still a fun read – 3 stars.

A third of the way in, the chunky, overspaced and simple novel Clarke (2022) by Holly Throsby had me annoyed by it’s lack of anything much. With chapters that alternated between two damaged neighbours in the small town of Clarke, there was an overplayed hopelessness about them which was tedious. I’m still not convinced it’s a very good book, but gradually the mystery of their investigation of a missing neighbour (based on the real-life story of Lynette Dawson) was uncovered, and the co-detectives were somewhat healed and I conceded I’d been won over. 3.5 stars.

I had a sense of deja-vu when reading The Fraud (2023) by Zadie Smith until I realised that I’d heard her discuss the novel on a podcast not long ago. On the whole, it was an interesting read, and the strong willed but flawed (and trapped) Scottish widow Mrs Touchet (the Targe) was likeable and complex (she bedded her brother in law and fading author William Ainsworth and his wife separately!). There was a mid-section (Volume 6) where I got distracted and a bit lost in the backstory of Bogle in Jamaica, but after that it was pretty much all about the adjacent real-life Tichborne Trial (1873) where a Wapping butcher Arthur Orton (by way of Wagga Wagga) made a claim to the Tichborne baronetcy and estates. Beautifully done – 4.5 stars.

A bit of a mixed bag this Cleveland Anthology (second edition) – put together by Piiparinen and Trubek. I had been putting off reading it since acquisition in 2018 on my sports trip to Ohio, and decided it was now or never. There were some great pieces in here, plus the expected, earnest, I-grew-up-in-Ohio-and-moved-away-but-I’ll-always-think-of-Ohio-as-home ones. What I didn’t expect was that it would make me want to revisit the city, since I thought I’d rid myself of any general U.S related travel-related interest thesedays. I don’t know if “Rust Belt Chic” is still a thing, but I bet there are still plenty of affordable places to buy and rough neighbourhoods to gentrify a little. That city brings out a weird, latent property renovator/speculator version of me – so much history and charm in the housing and neighbourhoods of Cleveland just waiting to be found and loved. 3 stars.

Now for my annual crime novel (courtesy of the Op Shop like most of these) with the awkward title of Blues for Outlaw Hearts and old Whores by Massimo Carlotto. I can’t say I’m a huge fan of the hardboiled style, where I get overwhelmed by the complexity (x double-crossed y who was working secretly with z who then had x investigated and tortured. He then revealed he worked with a, whose boss was b who struck a deal with z to get y and a exonerated but meant the end for a and x. It was dizzying at times trying to figure out who was in cahoots with whom, but along the way there was an unlikely Italian/Austrian love story which seemingly motivated an entire gang to kill a bunch of people so the couple could ride off into the sunset, only to have her leave him at a later point because that is just how things go. The author had a weird obsession with lyrics to blues songs, but generally the writing was sound and it left room for future escapades. 3.5 stars.